Robert Silverberg: A Case-Study of Openers

Last week, I wrote a piece about first lines, and how they're opening salutation of the conversation about to begin when a reader begins a new piece of fiction. In that essay, I used the example of Richard Matheson's I Am Legend as a prime example of a work with a great opening line.

I made an issue of this particular element because it is a skill that can both be learned and mastered. Most fiction writers (and Matheson is a great example), learned this ability by writing short stories.

Short stories are frequently the kind of work produced by many fiction writers at the start of their careers. Some continue to write them after they've become successful (Matheson did, Bradbury did, and Stephen Kind still does), but some don't. Short stories are a more difficult form; every word has to work. A spare word in a short story sticks out like a dandelion on a lawn. With this in mind, this economy of language, storywriters must learn to grab and keep reader attention with the fewest words, hence why the openings of short stories are so arresting.

When writers, if they so choose, move on to novels, much of the skill set carries over. This includes the ability to write a gripping opening sentence.

But novels are novels, and short stories are short stories. The two may both be prose fiction, but they are different forms. The biggest difference--literally--is length. Since novels offer greater space due to their greater wordcount, they can be more indulgent. They can also be more slowly paced, allowing for deeper character development and more detailed worldbuilding.

Thus, they don't need to be so upfront about their contents, but they can if they want to be.

An author that illustrates this is the SF Grand Master, Robert Silverberg.

Like all the SF writers who got their start in the Pulp Magazines, Silverberg wrote numerous short stories to make a living. When the publishing industry changed, and SF began appearing in book form, Silverberg made the transition. The skills he honed as a short story writer came with him as he began writing novels, and the beginnings of some of his novels show evidence of this. However, his not all of his novels begin in the same way, with a gripping first line.

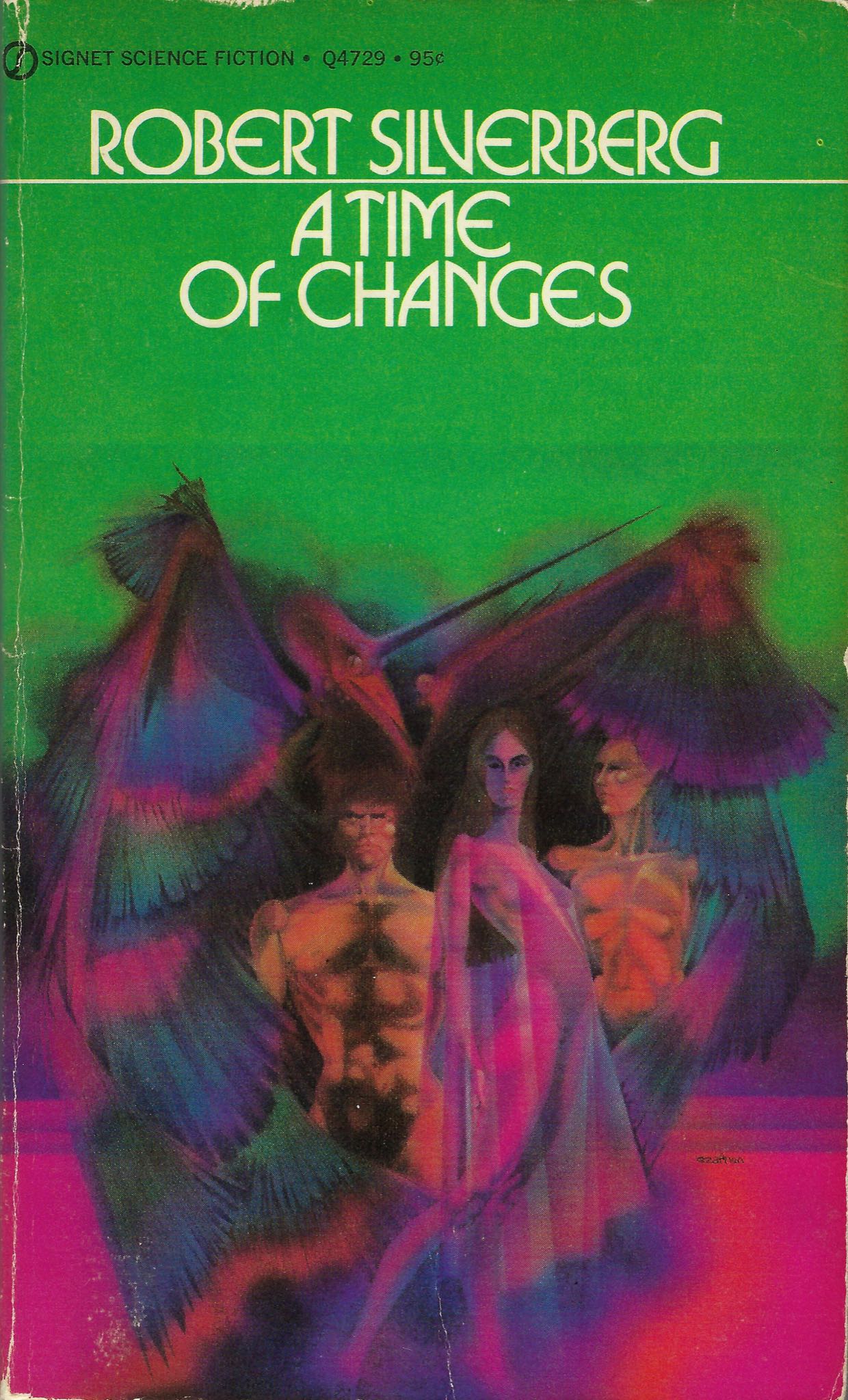

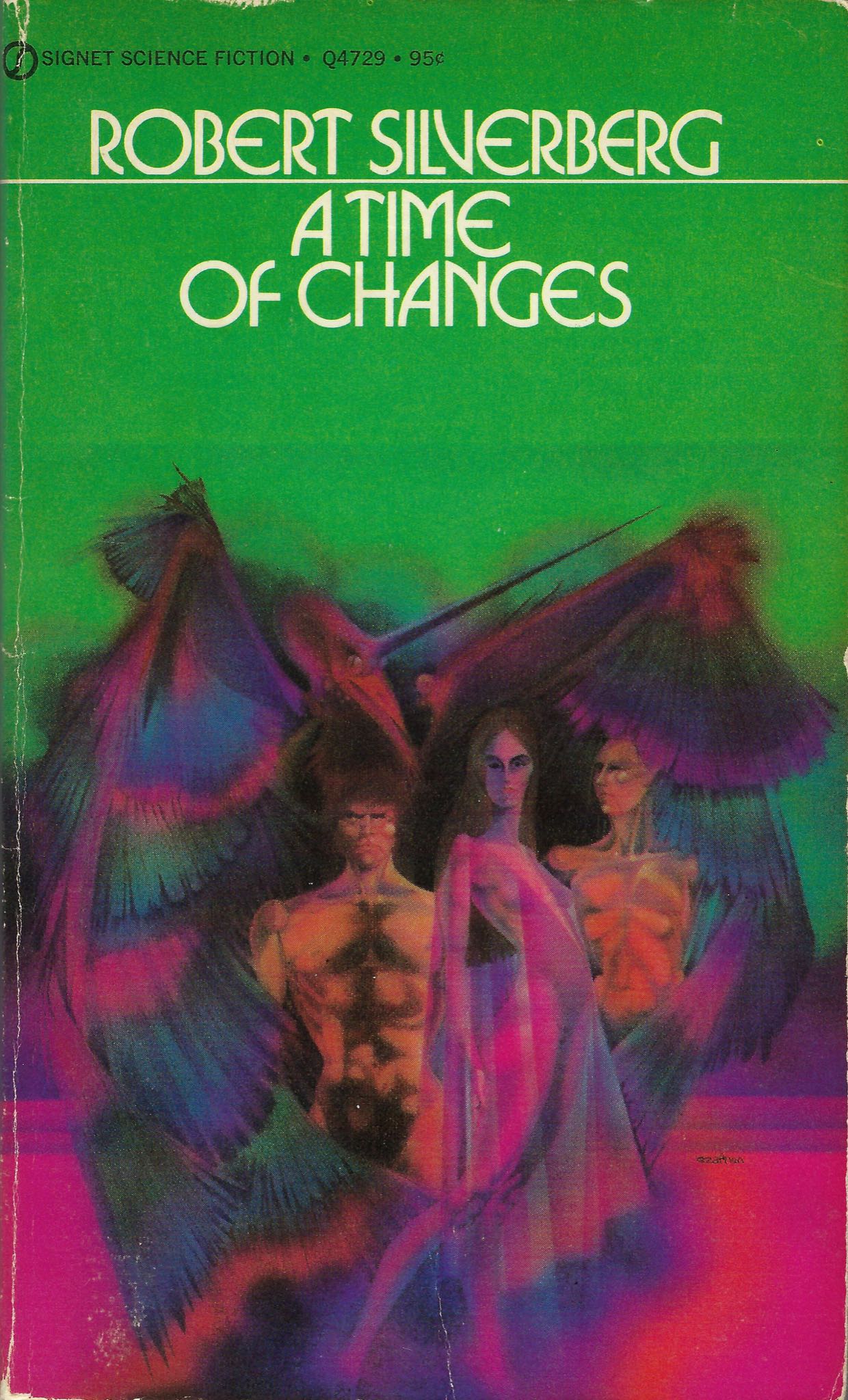

In his Nebula-award winning novel, A Time of Changes, Silverberg begins the story with the following sentence:

"I am Kinnall Darival and I mean to tell you all about myself."

I made an issue of this particular element because it is a skill that can both be learned and mastered. Most fiction writers (and Matheson is a great example), learned this ability by writing short stories.

Short stories are frequently the kind of work produced by many fiction writers at the start of their careers. Some continue to write them after they've become successful (Matheson did, Bradbury did, and Stephen Kind still does), but some don't. Short stories are a more difficult form; every word has to work. A spare word in a short story sticks out like a dandelion on a lawn. With this in mind, this economy of language, storywriters must learn to grab and keep reader attention with the fewest words, hence why the openings of short stories are so arresting.

When writers, if they so choose, move on to novels, much of the skill set carries over. This includes the ability to write a gripping opening sentence.

But novels are novels, and short stories are short stories. The two may both be prose fiction, but they are different forms. The biggest difference--literally--is length. Since novels offer greater space due to their greater wordcount, they can be more indulgent. They can also be more slowly paced, allowing for deeper character development and more detailed worldbuilding.

Thus, they don't need to be so upfront about their contents, but they can if they want to be.

An author that illustrates this is the SF Grand Master, Robert Silverberg.

Like all the SF writers who got their start in the Pulp Magazines, Silverberg wrote numerous short stories to make a living. When the publishing industry changed, and SF began appearing in book form, Silverberg made the transition. The skills he honed as a short story writer came with him as he began writing novels, and the beginnings of some of his novels show evidence of this. However, his not all of his novels begin in the same way, with a gripping first line.

In his Nebula-award winning novel, A Time of Changes, Silverberg begins the story with the following sentence:

"I am Kinnall Darival and I mean to tell you all about myself."

It's a simple first line, but some of the best are indeed simple. It's very reminiscent of a short story opener, but like any good story, long or short, it's a sentence that begs questions of the reader.

Who is this Kinnall Darival? That's an unusual name, a made up one clearly, so are we even in the contemporary world anymore or a fully fictitious one? And, why does he seem so compelled to speak of himself? On a word level, why does he use subjective pronouns three times in a single sentence--seems awfully conceited? Is it though, or is there something more to it?

All of these question are of course eventually answered in the novel, but in a single sentence, Silverberg has a reader gripped with curiosity. The desire to learn the answer to the main question--who is this Kinnall Darival and why must he tell us all about himself?--becomes the driving force that compels the reader forward.

A similar sentence can be found in a later novel in Silverberg's oeuvre titled Kingdoms of the Wall:

"This is the book of Poilar Crookleg, I who have been to the roof of the World at the top of the Wall and have felt the terrible fire of revelation there."

Who is this Kinnall Darival? That's an unusual name, a made up one clearly, so are we even in the contemporary world anymore or a fully fictitious one? And, why does he seem so compelled to speak of himself? On a word level, why does he use subjective pronouns three times in a single sentence--seems awfully conceited? Is it though, or is there something more to it?

All of these question are of course eventually answered in the novel, but in a single sentence, Silverberg has a reader gripped with curiosity. The desire to learn the answer to the main question--who is this Kinnall Darival and why must he tell us all about himself?--becomes the driving force that compels the reader forward.

A similar sentence can be found in a later novel in Silverberg's oeuvre titled Kingdoms of the Wall:

"This is the book of Poilar Crookleg, I who have been to the roof of the World at the top of the Wall and have felt the terrible fire of revelation there."

Again, we have a first person voice--a viewpoint Silverberg favors because of its feeling of immediate intimacy--and again, questions are begged.

Who is Poilar Crookleg? What is this place, the roof of the world at the top of the wall? What's so significant about this Wall that its deserving of capitalization? What world are we even residing in, a speculative one, a fantastical one? And what is this terrible fire of revelation that Poilar felt?

Again, all of the questions get answered, but only as the book goes on.

A third novel however, breaks the apparent trend in Silverberg's lines. In the novel Dying Inside, which was published between the previous two examples, Silverberg doesn't make use of an overly gripping first line. In fact, the very first line is quite unremarkable:

Who is Poilar Crookleg? What is this place, the roof of the world at the top of the wall? What's so significant about this Wall that its deserving of capitalization? What world are we even residing in, a speculative one, a fantastical one? And what is this terrible fire of revelation that Poilar felt?

Again, all of the questions get answered, but only as the book goes on.

A third novel however, breaks the apparent trend in Silverberg's lines. In the novel Dying Inside, which was published between the previous two examples, Silverberg doesn't make use of an overly gripping first line. In fact, the very first line is quite unremarkable:

"So, then, I have to go downtown to the University and forage for dollars again."

This line is no where near as dramatic as the previous two. There's no odd name, no dramatic urgency. If anything, there's simply a tone of apathy and unenthusiasm. Yet, even for such an undramatic sentence, it still begs questions:

Who is this person speaking? They're going to a university, so does that mean we're in a fairly familiar setting? Why must this person go to the university in particular to make money? They can't be a teacher or TA because they used the word forage, so what are they doing for money?

What Silverberg does with the beginning of Dying Inside is take advantage of the novel form's length. Since a novel has more space, and therefore, greater time to impact the reader, a novel can actually be more subtle in certain areas, including its opening. Here, he instead opts to string the reader along a little more, knowing full well he need not worry about losing them in a matter of paragraphs, but in pages.

The beginning continues:

"It doesn't take much cash to keep me going--$200 a month will do nicely--but I'm running low, and I don't dare try to borrow from my sister again. The students will shortly be needing their first term papers of the semester; that's always a steady business. The weary, eroding brain of David Selig is once more for hire."

In a paragraph, Silverberg answers several of the questions his first line begs. We know the narrator's name is David Selig. We know he goes to the university, not to teach, but to write term papers for students too lazy to write them themselves. We also know he has family, but its likely they're not on the best of terms. Still, more questions are begged.

Why would David describe his brain as eroding? Such an odd word to use--wouldn't aging be better? Is he perhaps sick?

The beginning continues on:

"I should be able to pick up $75 worth of work on this lovely golden October morning. The air is crisp and clear. A high-pressure system covers New York City, banishing humidity and haze. In such weather my fading powers still flourish. Let us go then, you and I, when the morning is spread out against the sky. To the Broadway IRT subway. Have your tokens ready. please."

Now we know where we reside. Indeed, we are in the streets of New York City itself, We know the time of year. Yet still, more questions are begged.

What does he mean, you and I? Is it just an allusion to Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," or is it more significant? Also, what does he mean by fading powers? Is it just a matter of mental ability? Is he old and suffering dementia or Alzheimer's? Is it cancer, or is it perhaps something else?

Well, to find that out, you'd have to read on.

No matter the approach--the immediately gripping opening or the more subtle opening--one thing that every story must do, and that Silverberg manages to do whenever he begins his works, is navigate that tightrope of begging question of the reader and providing answers for the raised questions.

If you can manage to learn that, then the writing of fiction becomes just that much a less daunting task.

This line is no where near as dramatic as the previous two. There's no odd name, no dramatic urgency. If anything, there's simply a tone of apathy and unenthusiasm. Yet, even for such an undramatic sentence, it still begs questions:

Who is this person speaking? They're going to a university, so does that mean we're in a fairly familiar setting? Why must this person go to the university in particular to make money? They can't be a teacher or TA because they used the word forage, so what are they doing for money?

What Silverberg does with the beginning of Dying Inside is take advantage of the novel form's length. Since a novel has more space, and therefore, greater time to impact the reader, a novel can actually be more subtle in certain areas, including its opening. Here, he instead opts to string the reader along a little more, knowing full well he need not worry about losing them in a matter of paragraphs, but in pages.

The beginning continues:

"It doesn't take much cash to keep me going--$200 a month will do nicely--but I'm running low, and I don't dare try to borrow from my sister again. The students will shortly be needing their first term papers of the semester; that's always a steady business. The weary, eroding brain of David Selig is once more for hire."

In a paragraph, Silverberg answers several of the questions his first line begs. We know the narrator's name is David Selig. We know he goes to the university, not to teach, but to write term papers for students too lazy to write them themselves. We also know he has family, but its likely they're not on the best of terms. Still, more questions are begged.

Why would David describe his brain as eroding? Such an odd word to use--wouldn't aging be better? Is he perhaps sick?

The beginning continues on:

"I should be able to pick up $75 worth of work on this lovely golden October morning. The air is crisp and clear. A high-pressure system covers New York City, banishing humidity and haze. In such weather my fading powers still flourish. Let us go then, you and I, when the morning is spread out against the sky. To the Broadway IRT subway. Have your tokens ready. please."

Now we know where we reside. Indeed, we are in the streets of New York City itself, We know the time of year. Yet still, more questions are begged.

What does he mean, you and I? Is it just an allusion to Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," or is it more significant? Also, what does he mean by fading powers? Is it just a matter of mental ability? Is he old and suffering dementia or Alzheimer's? Is it cancer, or is it perhaps something else?

Well, to find that out, you'd have to read on.

No matter the approach--the immediately gripping opening or the more subtle opening--one thing that every story must do, and that Silverberg manages to do whenever he begins his works, is navigate that tightrope of begging question of the reader and providing answers for the raised questions.

If you can manage to learn that, then the writing of fiction becomes just that much a less daunting task.