The Room

I stated in my first essay that I would refrain from talking about things that I don't like on here. However, considering that I mentioned Trump on here once, that promise to myself is pretty much broken.

And since I've broken it once, I might as well break it again, but only because it'll allow me to talk about something I like.

One of my friends is my buddy Will (who happens to be the inamorato of my best friend, Val). Will is, among other things, what's known as a film buff. What exactly is that? Well, the British Comedian, Bob Monkhouse, once defined a film buff as, "Someone who will intentionally watch a bad film." If such a definition is apt, then Will is a prime example.

Every once in a while, when I go to hang out at his home, he'll occasionally rope me into watching a movie. I never turn down such an opportunity. Movies, especially good movie, like good TV, are just as enjoyable an experience as reading a good book. They pull you out of yourself and into the world of the story. Some of Will's choice have been indeed good (my first viewing of Jordan Peele's Get Out was in his company), but some of them are--how do I say this without being blunt?--of questionable quality.

One such film was Tommy Wiseau's infamous The Room.

Will and Val had recently seen the biopic, The Disaster Artist, starring James and David Franco about the making of this film (which ironically was more successful than the subject of the film had been), and Will had apparently become curious about what the actual film was like. What made it so bad that many had called it, "the best worst movie ever made"? So they did. And they lived through it.

When I visited them though, Will saw a chance for something enjoyable: the opportunity to inflict a form of psychological torture on someone who could endure it. That someone, of course, was me.

Will being a film buff could watch a bad film sincerely. I, however, am NOT a film buff. When I'm presented with a bad movie, I can only watch it one way: ironically. This means that when I watch a bad movie, and every time a moment on the screen occurs that I find particularly horrendous, I turn to the person next to me and make a joke about it.

Still, after we finished it (and we did watch it all the way to the end), I started to wonder if there actually was a potential half-decent movie somewhere in this garbage-fire I'd just spent 99 minutes of my life watching. And, I came to the conclusion that there might be. I don't think it would've been a Gone with the Wind, a Psycho, or a Citizen Kane, but it could've been a film that, at least, made back its budget.

Now, before I go further, let me explain. I'm not just going to rip this film a new one. It's been around for 15 years--can you believe that?--and in that decade and a half interval, plenty of people have already done only that. Instead, I want to actually look at it as a piece of work and how it could have benefitted from a little friendly, but constructive criticism, had Wiseau, the writer, director, star, and producer of the film been inclined to take.

(If, however, you'd like to skip my spiel and only see someone rip this film a new one, I'd recommend the Nostalgia Critic's review of the movie. If not, keep reading...and then come back and watch it.)

In fiction writing, the step in the process that's frequently given the greatest emphasis is "Rewriting/Revision". This is, as I've said before and will repeat until I'm dead, the part of the writing process where you, the author, get to look like a genius. Revision is where you can go back, usually after you've produced a complete manuscript (not every writer does this, but most do) and review the whole thing, find the flaws, and fix them.

The equivalent in filmmaking, as I understand it with only a lay education in the process, is actually two parts, one at the beginning and one at the end: pre-production, during which the script gets rewritten, cast is decided, and rehearsals take place, and editing, where the editor and direct review the finish film by pieceing together the best takes and add the background score.

No matter what you call it, the use of the processes remains the same: fixing issues to make the story more compelling. (Though, for the sake of familiarity, I'll give my revision suggestions using my fiction writing lingo).

To begin the process, we first have to figure out what Wiseau's film was supposed to be.

Having seen it, I'd classify it as a "romantic tragedy," where a seemingly stable relationship is eventually fractured by the discovery of an unfaithful love triangle, leading to the suicide of one of the people involved. By figuring what the story is supposed to be, we are then able to determine what the "heart of the story" is.

In this case, that's simple: the eventual dissolution of the relationship and the understanding of both who's involved, how it happened, and why. These are the elements of the story that then beg questions from the audience--in this case, the viewing audience--experiencing it.

Since we now have the heart, we can do away with all the other things that do not serve to propel this narrative forward, and the story of this film is riddled with such things. Wiseau scatters this film with subplots and underdeveloped side characters who only detract and distract from the main story (see the notable and badly acted "breast cancer" revelation scene for an example or even Denny's whole narrative as well). If we were to remove all that, keeping only what moves the story forward, then the improvement could be vast. (I'll get into this more soon).

Now that we've established what the "heart of the story" is, we then have to determine the answers for all these question begging elements.

Let's start with who. The three corners in this love triangle story are Johnny (played by Wiseau), Mark, Johnny's best friend (played by Greg Sestero), and Lisa, Johnny's fiancé, who cheats on him with Mark (played by Juliette Danielle). With these three characters--the aspect of story that I believe to be the most important--you have the heart of the story. Their interactions form the emotional center of the story, the element to which we as viewers are supposed to relate. They also provide the epicenter for the conflict of the story. Given this is a tale of faithlessness and its destructive power, the uncovering of such goings on by one character and the understanding of why the other two do it should form the backbone of narrative.

Then we have how, which is simple as well. We know that Lisa is not satisfied with Johnny, who despite his devotion to her, is not making her happy. Thus, she turns to Mark. She calls in on the phone, asks him to come over, and after a less-that-convincing attempt at refusal, Mark succumbs to her seductive charms, and their affair begins.

Finally, we have the why. Or, in this case, we don't. The two characters in this situation more than anyone, even more than Johnny, are Lisa and Mark. We need context into how their lives intertwine with Johnny's.

Mark's regular refrain ("Johnny's my best friend.") is not enough to add to the drama. It give us a clue that he feels guilty about In that case, I'd recommend using (and I can't believe I am, since I hate this advice, but it is fitting for a movie), the old piece of fiction advice: SHOW, DON'T TELL. We need a scene showing his and Johnny's relationship in action. I suppose the argument could be made that the eventual attack against Denny was supposed to be that, but it wasn't enough.

Speaking of enough, we never come to understand why it was that Lisa was not satisfied with Johnny. She simply explains it to her mother, time and again, that he's boring, and because of this, Danielle's performance actually comes across as almost a case of split-personality. When she's with Johnny, she appears devoted, but whenever he's not in frame, she's cold, vindictive, almost cruel. Yet, we never understand why (again, SHOW, DON'T TELL). Could it have been because Johnny wasn't a bad boy? Is it because he's too overly devoted? We never get an answer, and to improve this story, we'd need one. (Perhaps had we not spent what felt like fifteen minutes watching them make love, it wouldn't seem this way, but there you go).

In fact, that's one problem the story's whole cast of characters suffer from: underdevelopment. We don't come to understand anything past the surface of what they say and initially present. We get none of their background, none of their dreams, nothing. We don't even come to understand how any of them met. (Of course, since it's really just the three central characters we need to understand, this is a moot point on the others).

To conclude simply, had Wiseau spent more time focusing on developing his three central roles and how they relate to one another, the final climactic scene and the meaning it carried--that a room where happiness resides can also be a sight of betrayal, heartbreak, and death--would've had an actual impact rather than feeling forced and unsatisfying.

However, all of this is moot. Wiseau's movie, on the wider, cinematic level has its flaws, flaws for which I, not being a filmmaker cannot recommend revisions. Some of the scenes--like the love making scenes--are simply too long. The dialogue is far from being Aaron Sorkin-esque. And the score, especially during the love making scenes, sounds like something out of a 1970s porno film.

Then there's the acting. How best can I describe it? Tommy Wiseau should've found a better actor (like James Franco) to play his role instead of insisting on being the absolute center of this film.

He also should've considered finding a better screenwriter (like Aaron Sorkin). You cannot make a good film from a bad script. You can make a bad film from a good script, but the opposite is impossible. Had he allowed someone else a second look at his screenplay, he may have gotten a good film in this end.

Instead, he got The Room.

And since I've broken it once, I might as well break it again, but only because it'll allow me to talk about something I like.

One of my friends is my buddy Will (who happens to be the inamorato of my best friend, Val). Will is, among other things, what's known as a film buff. What exactly is that? Well, the British Comedian, Bob Monkhouse, once defined a film buff as, "Someone who will intentionally watch a bad film." If such a definition is apt, then Will is a prime example.

Every once in a while, when I go to hang out at his home, he'll occasionally rope me into watching a movie. I never turn down such an opportunity. Movies, especially good movie, like good TV, are just as enjoyable an experience as reading a good book. They pull you out of yourself and into the world of the story. Some of Will's choice have been indeed good (my first viewing of Jordan Peele's Get Out was in his company), but some of them are--how do I say this without being blunt?--of questionable quality.

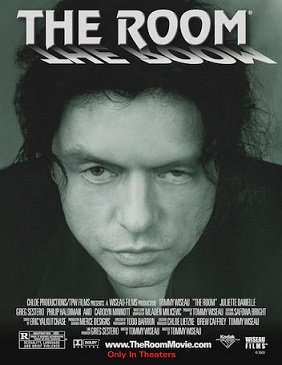

|

| Jesus, look at that face. |

Will and Val had recently seen the biopic, The Disaster Artist, starring James and David Franco about the making of this film (which ironically was more successful than the subject of the film had been), and Will had apparently become curious about what the actual film was like. What made it so bad that many had called it, "the best worst movie ever made"? So they did. And they lived through it.

When I visited them though, Will saw a chance for something enjoyable: the opportunity to inflict a form of psychological torture on someone who could endure it. That someone, of course, was me.

Will being a film buff could watch a bad film sincerely. I, however, am NOT a film buff. When I'm presented with a bad movie, I can only watch it one way: ironically. This means that when I watch a bad movie, and every time a moment on the screen occurs that I find particularly horrendous, I turn to the person next to me and make a joke about it.

Still, after we finished it (and we did watch it all the way to the end), I started to wonder if there actually was a potential half-decent movie somewhere in this garbage-fire I'd just spent 99 minutes of my life watching. And, I came to the conclusion that there might be. I don't think it would've been a Gone with the Wind, a Psycho, or a Citizen Kane, but it could've been a film that, at least, made back its budget.

Now, before I go further, let me explain. I'm not just going to rip this film a new one. It's been around for 15 years--can you believe that?--and in that decade and a half interval, plenty of people have already done only that. Instead, I want to actually look at it as a piece of work and how it could have benefitted from a little friendly, but constructive criticism, had Wiseau, the writer, director, star, and producer of the film been inclined to take.

(If, however, you'd like to skip my spiel and only see someone rip this film a new one, I'd recommend the Nostalgia Critic's review of the movie. If not, keep reading...and then come back and watch it.)

In fiction writing, the step in the process that's frequently given the greatest emphasis is "Rewriting/Revision". This is, as I've said before and will repeat until I'm dead, the part of the writing process where you, the author, get to look like a genius. Revision is where you can go back, usually after you've produced a complete manuscript (not every writer does this, but most do) and review the whole thing, find the flaws, and fix them.

The equivalent in filmmaking, as I understand it with only a lay education in the process, is actually two parts, one at the beginning and one at the end: pre-production, during which the script gets rewritten, cast is decided, and rehearsals take place, and editing, where the editor and direct review the finish film by pieceing together the best takes and add the background score.

No matter what you call it, the use of the processes remains the same: fixing issues to make the story more compelling. (Though, for the sake of familiarity, I'll give my revision suggestions using my fiction writing lingo).

To begin the process, we first have to figure out what Wiseau's film was supposed to be.

Having seen it, I'd classify it as a "romantic tragedy," where a seemingly stable relationship is eventually fractured by the discovery of an unfaithful love triangle, leading to the suicide of one of the people involved. By figuring what the story is supposed to be, we are then able to determine what the "heart of the story" is.

In this case, that's simple: the eventual dissolution of the relationship and the understanding of both who's involved, how it happened, and why. These are the elements of the story that then beg questions from the audience--in this case, the viewing audience--experiencing it.

Since we now have the heart, we can do away with all the other things that do not serve to propel this narrative forward, and the story of this film is riddled with such things. Wiseau scatters this film with subplots and underdeveloped side characters who only detract and distract from the main story (see the notable and badly acted "breast cancer" revelation scene for an example or even Denny's whole narrative as well). If we were to remove all that, keeping only what moves the story forward, then the improvement could be vast. (I'll get into this more soon).

Now that we've established what the "heart of the story" is, we then have to determine the answers for all these question begging elements.

Let's start with who. The three corners in this love triangle story are Johnny (played by Wiseau), Mark, Johnny's best friend (played by Greg Sestero), and Lisa, Johnny's fiancé, who cheats on him with Mark (played by Juliette Danielle). With these three characters--the aspect of story that I believe to be the most important--you have the heart of the story. Their interactions form the emotional center of the story, the element to which we as viewers are supposed to relate. They also provide the epicenter for the conflict of the story. Given this is a tale of faithlessness and its destructive power, the uncovering of such goings on by one character and the understanding of why the other two do it should form the backbone of narrative.

Then we have how, which is simple as well. We know that Lisa is not satisfied with Johnny, who despite his devotion to her, is not making her happy. Thus, she turns to Mark. She calls in on the phone, asks him to come over, and after a less-that-convincing attempt at refusal, Mark succumbs to her seductive charms, and their affair begins.

Finally, we have the why. Or, in this case, we don't. The two characters in this situation more than anyone, even more than Johnny, are Lisa and Mark. We need context into how their lives intertwine with Johnny's.

Mark's regular refrain ("Johnny's my best friend.") is not enough to add to the drama. It give us a clue that he feels guilty about In that case, I'd recommend using (and I can't believe I am, since I hate this advice, but it is fitting for a movie), the old piece of fiction advice: SHOW, DON'T TELL. We need a scene showing his and Johnny's relationship in action. I suppose the argument could be made that the eventual attack against Denny was supposed to be that, but it wasn't enough.

Speaking of enough, we never come to understand why it was that Lisa was not satisfied with Johnny. She simply explains it to her mother, time and again, that he's boring, and because of this, Danielle's performance actually comes across as almost a case of split-personality. When she's with Johnny, she appears devoted, but whenever he's not in frame, she's cold, vindictive, almost cruel. Yet, we never understand why (again, SHOW, DON'T TELL). Could it have been because Johnny wasn't a bad boy? Is it because he's too overly devoted? We never get an answer, and to improve this story, we'd need one. (Perhaps had we not spent what felt like fifteen minutes watching them make love, it wouldn't seem this way, but there you go).

In fact, that's one problem the story's whole cast of characters suffer from: underdevelopment. We don't come to understand anything past the surface of what they say and initially present. We get none of their background, none of their dreams, nothing. We don't even come to understand how any of them met. (Of course, since it's really just the three central characters we need to understand, this is a moot point on the others).

To conclude simply, had Wiseau spent more time focusing on developing his three central roles and how they relate to one another, the final climactic scene and the meaning it carried--that a room where happiness resides can also be a sight of betrayal, heartbreak, and death--would've had an actual impact rather than feeling forced and unsatisfying.

However, all of this is moot. Wiseau's movie, on the wider, cinematic level has its flaws, flaws for which I, not being a filmmaker cannot recommend revisions. Some of the scenes--like the love making scenes--are simply too long. The dialogue is far from being Aaron Sorkin-esque. And the score, especially during the love making scenes, sounds like something out of a 1970s porno film.

Then there's the acting. How best can I describe it? Tommy Wiseau should've found a better actor (like James Franco) to play his role instead of insisting on being the absolute center of this film.

He also should've considered finding a better screenwriter (like Aaron Sorkin). You cannot make a good film from a bad script. You can make a bad film from a good script, but the opposite is impossible. Had he allowed someone else a second look at his screenplay, he may have gotten a good film in this end.

Instead, he got The Room.

Comments