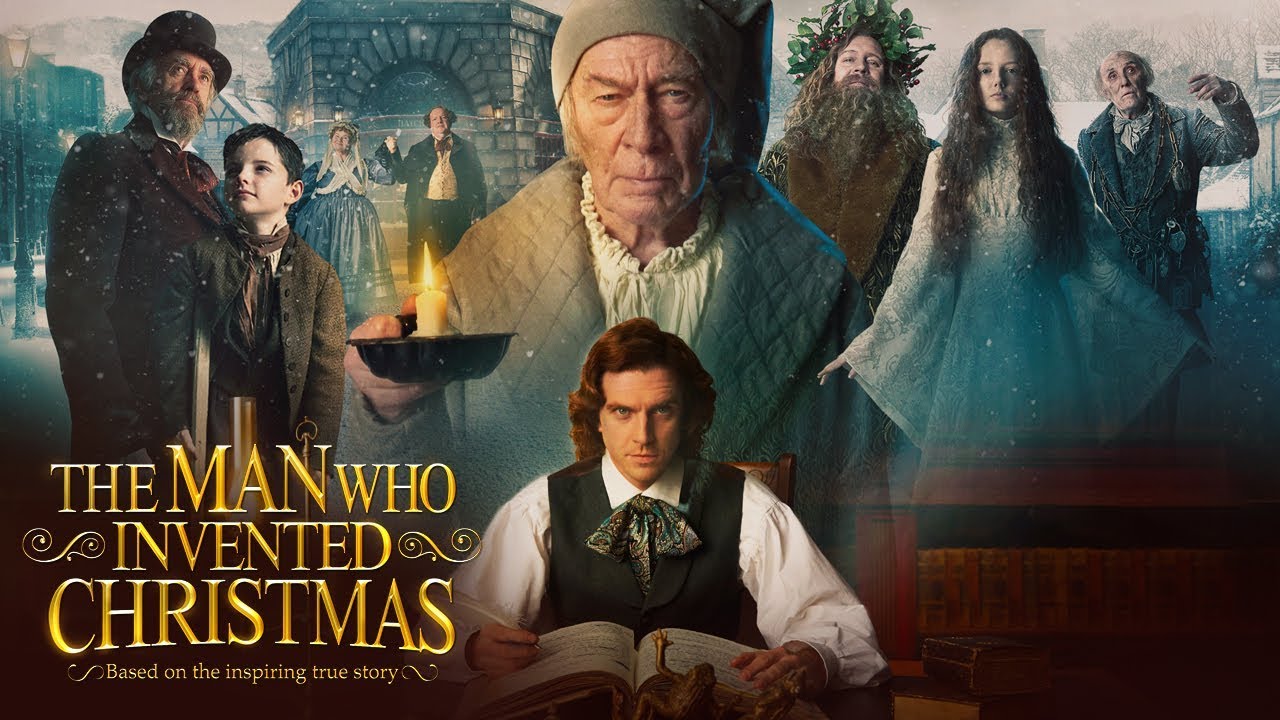

The Problems and Virtues of The Man Who Invented Christmas

One of my favorite stories in all of literature is A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. It's a story I've known about since I was a little kid. I think my first exposure to it was, again as a kid, via the Disney adaptation, Mickey's Christmas Carol, which remains my favorite version of the story, apart from the original.

When I got older, and went on to study literature, I became interested in understanding how Dickens came to write this inimitable "scary ghost story" of the Christmas Season. It's this knowledge that caused my slightly negative reaction to the Bleeker Street film that tells the tale of how Dickens composed the novella, The Man Who Invented Christmas.

In the end, though the book was successful, it wasn't successful in the way Dickens wanted or needed it to be for his own financial standing.

It wouldn't be until he started writing his next novel Dombey and Son, as well as his other Christmas Stories, The Chimes, The Cricket and the Hearth, The Battle for Life, and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain before it, that Dickens would achieve that enviable position of being a writer without any financial worries.

Finally, there's the fact that the film ends with his family fully reunited.

When I got older, and went on to study literature, I became interested in understanding how Dickens came to write this inimitable "scary ghost story" of the Christmas Season. It's this knowledge that caused my slightly negative reaction to the Bleeker Street film that tells the tale of how Dickens composed the novella, The Man Who Invented Christmas.

|

(As a side note, I've noticed recently that Bleeker Street seems have a predilection for producing films about writers e.g. Trumbo, Colette, and this film. Interesting.)

|

Now, I'm going to totally spoil the movie for everyone; however, if you have Amazon Prime or Hulu, you can go and watch it now for free, and then you can read my thoughts on it here. (I'll wait).

(To the returnees, welcome back. If you have, skip the next few paragraphs. If you haven't bothered to watch it, keep reading).

Here's the set up. The film opens with us, the viewers seeing Charles Dickens (portrayed in his young years by Downton Abbey's Dan Stevens) in the middle of a pickle. His previous three books, the novels Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit, as well as his travel book, American Notes based on his first great tour of America, have flopped. He's in a big financial bind and needs to make money fast. Thus, he decides to write a nice little book for the Christmas Season, which at the time is a mere six weeks away and is considered a "minor holiday". His publishers are dismissive of the idea, since they see very little value in a Christmas book (imagine what they'd think today).

Enraged, Dickens decides to write his book anyway, a ghost story about a miser, to which eventually he gives the title A Christmas Carol. Slowly, over the course of six weeks, Dickens composes the book, taking inspiration for the characters and the plot from the world he sees around him. His first real creation is, of course, the immortal Ebenezer Scrooge, born literally into life (as played by Christopher Plummer) from several scenes early in the film once Dickens evokes him with his name.

The rest of the movie follows Dickens as he struggles to finish the book. More so, he's haunted by the ghosts of his own past. As a child, he was abandoned by his family to a blacking factory in order to dig them out of debt, something that continuously pops up in his work. These ghosts put strains on his family life, his marriage, and his relationship with his parents (they practically drove him to create and work at the pace he did for fear of ending up in the poor house again). Eventually though, he does, and the book is a runaway success, and all the problems--Dickens' demons, the strains between him and his family, and his financial issues--are solved.

And that's where my problem with the film starts.

Before I do what Neil DeGrasse Tyson does to science fiction films, let me explain what I actually like about this film.

Its title is an apt one because, for Victorian England, Charles Dickens—post A Christmas Carol—was as synonymous with the holiday as Santa Claus (or Father Christmas). To many, he was the one, with that single story, who created the modern idea of how to celebrate Christmas that persists to this day. Christmas, as Dickens saw it, was the one day when all the worries of the world should be pushed aside, and people should get along. Charity should be a priority. Family should be the focus. He became so linked with the holiday that he actually wrote four more stories specifically for the Christmas holidays after Christmas Carol, none of which are nearly as remembered as the first. With this story, Dickens captured the zeitgeist of his time, and, concurrently, immortalized himself. I'm certain that, had everything else he'd written been lost to obscurity, we'd still be reading A Christmas Carol.

The film is also one of the few that depicts the act of writing fiction in a fairly accurate manner. Stories, like the Carol, are not born of one idea. They're composed of a multitude of much smaller ideas, for characters, for settings, for plot developments, for dialogue, which writers then carefully tie together into verbal tapestries.

Also, it brings that classic cliché of characters literally taking on a life of their own and literalizes it. Many of the people Dickens actually interacts with in the film are not "real people." They're specters of his own imagination. But, for many writers, that cliché is a cliché for a reason. They hear and speak to their characters, trying to figure out who they are, so they figure out where their story should go. Not only does this stylistic choice make for some of the funniest and most moving scenes in the film, but it externalizes what is otherwise a highly internal, and therefore unfilmable, process of thought. And it works well.

Dan Stevens' performance in particular is one I love. He really captures that mercurial temperament common among writers. When his story is flowing well, he's in a state of elation, but when it's not, he's as downcast as Marley is dead. By all accounts, Dickens himself suffered such mood-swings throughout his life. Many psychologists and psychiatrists in fact now believe he may have suffered from Bipolar Disorder, and Stevens captures the essence of it well.

(To the returnees, welcome back. If you have, skip the next few paragraphs. If you haven't bothered to watch it, keep reading).

Here's the set up. The film opens with us, the viewers seeing Charles Dickens (portrayed in his young years by Downton Abbey's Dan Stevens) in the middle of a pickle. His previous three books, the novels Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit, as well as his travel book, American Notes based on his first great tour of America, have flopped. He's in a big financial bind and needs to make money fast. Thus, he decides to write a nice little book for the Christmas Season, which at the time is a mere six weeks away and is considered a "minor holiday". His publishers are dismissive of the idea, since they see very little value in a Christmas book (imagine what they'd think today).

Enraged, Dickens decides to write his book anyway, a ghost story about a miser, to which eventually he gives the title A Christmas Carol. Slowly, over the course of six weeks, Dickens composes the book, taking inspiration for the characters and the plot from the world he sees around him. His first real creation is, of course, the immortal Ebenezer Scrooge, born literally into life (as played by Christopher Plummer) from several scenes early in the film once Dickens evokes him with his name.

The rest of the movie follows Dickens as he struggles to finish the book. More so, he's haunted by the ghosts of his own past. As a child, he was abandoned by his family to a blacking factory in order to dig them out of debt, something that continuously pops up in his work. These ghosts put strains on his family life, his marriage, and his relationship with his parents (they practically drove him to create and work at the pace he did for fear of ending up in the poor house again). Eventually though, he does, and the book is a runaway success, and all the problems--Dickens' demons, the strains between him and his family, and his financial issues--are solved.

And that's where my problem with the film starts.

Before I do what Neil DeGrasse Tyson does to science fiction films, let me explain what I actually like about this film.

Its title is an apt one because, for Victorian England, Charles Dickens—post A Christmas Carol—was as synonymous with the holiday as Santa Claus (or Father Christmas). To many, he was the one, with that single story, who created the modern idea of how to celebrate Christmas that persists to this day. Christmas, as Dickens saw it, was the one day when all the worries of the world should be pushed aside, and people should get along. Charity should be a priority. Family should be the focus. He became so linked with the holiday that he actually wrote four more stories specifically for the Christmas holidays after Christmas Carol, none of which are nearly as remembered as the first. With this story, Dickens captured the zeitgeist of his time, and, concurrently, immortalized himself. I'm certain that, had everything else he'd written been lost to obscurity, we'd still be reading A Christmas Carol.

The film is also one of the few that depicts the act of writing fiction in a fairly accurate manner. Stories, like the Carol, are not born of one idea. They're composed of a multitude of much smaller ideas, for characters, for settings, for plot developments, for dialogue, which writers then carefully tie together into verbal tapestries.

Also, it brings that classic cliché of characters literally taking on a life of their own and literalizes it. Many of the people Dickens actually interacts with in the film are not "real people." They're specters of his own imagination. But, for many writers, that cliché is a cliché for a reason. They hear and speak to their characters, trying to figure out who they are, so they figure out where their story should go. Not only does this stylistic choice make for some of the funniest and most moving scenes in the film, but it externalizes what is otherwise a highly internal, and therefore unfilmable, process of thought. And it works well.

Dan Stevens' performance in particular is one I love. He really captures that mercurial temperament common among writers. When his story is flowing well, he's in a state of elation, but when it's not, he's as downcast as Marley is dead. By all accounts, Dickens himself suffered such mood-swings throughout his life. Many psychologists and psychiatrists in fact now believe he may have suffered from Bipolar Disorder, and Stevens captures the essence of it well.

Christopher Plummer's Scrooge, who is both the classic character and also the personification of Dickens' own doubts and demons, a sort of anti-muse who both inspires and haunts Dickens throughout the film. He is both true to the source character and his own great creation that stands alongside every other Scrooge in history, bringing out a menace and darkness that's there in the book if you read carefully enough.

You can see there's lots to love about this movie. It's no wonder it has an 80% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Still, I have my hang-ups, and, as I mentioned earlier, one hang-up is the ending.

As a "Christmas Movie" it's understandable that this film has a happy ending. Also, given that this film is a historical drama, it's understandable why the writers took liberties with what actually happened. However, just on a historical level, it's a completely wrong ending. (The vid below sums it all up):

Anyone who knows the Dickens' biography knows that it's true he wrote the story to help get him out of debt. With several flops behind him, he was rather desperate. The problem was that it didn't.

Unlike his novels, Dickens published the Carol as a book, rather than serializing it. It was the serialization that allowed his books to reach a wide, and largely illiterate, audience. Books, at the time, especially in England where paper's been (historically) a commodity, were incredibly expensive. In addition to that, the color illustrations, red-leather and gilded lettering, golden trim design made the final book incredibly expensive to print.

Thus, even though the book sold out, by the time the costs were covered, Dickens received very little money.

In addition, almost immediately, other people adapted the story for the stage, another wide appealing form of entertainment. Copyright laws were not what they are now (there's a scene in the film that touches on this), so Dickens couldn't profit from the adaptation rights.

You can see there's lots to love about this movie. It's no wonder it has an 80% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Still, I have my hang-ups, and, as I mentioned earlier, one hang-up is the ending.

As a "Christmas Movie" it's understandable that this film has a happy ending. Also, given that this film is a historical drama, it's understandable why the writers took liberties with what actually happened. However, just on a historical level, it's a completely wrong ending. (The vid below sums it all up):

Anyone who knows the Dickens' biography knows that it's true he wrote the story to help get him out of debt. With several flops behind him, he was rather desperate. The problem was that it didn't.

Unlike his novels, Dickens published the Carol as a book, rather than serializing it. It was the serialization that allowed his books to reach a wide, and largely illiterate, audience. Books, at the time, especially in England where paper's been (historically) a commodity, were incredibly expensive. In addition to that, the color illustrations, red-leather and gilded lettering, golden trim design made the final book incredibly expensive to print.

Thus, even though the book sold out, by the time the costs were covered, Dickens received very little money.

In addition, almost immediately, other people adapted the story for the stage, another wide appealing form of entertainment. Copyright laws were not what they are now (there's a scene in the film that touches on this), so Dickens couldn't profit from the adaptation rights.

In the end, though the book was successful, it wasn't successful in the way Dickens wanted or needed it to be for his own financial standing.

It wouldn't be until he started writing his next novel Dombey and Son, as well as his other Christmas Stories, The Chimes, The Cricket and the Hearth, The Battle for Life, and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain before it, that Dickens would achieve that enviable position of being a writer without any financial worries.

Finally, there's the fact that the film ends with his family fully reunited.

Now, of course, Dickens at this time had no reason to believe he'd ever leave his wife Catherine, but about a decade later, after the publication of David Copperfield, he did. The Ralph Fiennes film The Invisible Woman tells the tale of the Mistress Dickens took the last 13 years of his life. This affair led to the dissolution of his family; in one of his more panicked turns of mood, convinced if he remained with Catherine that his creativity would leave him, he left her for a young actress. More so, he forbade anyone his numerous children from speaking to her or even seeing her. It's a cruel sliver of Dickens' personality that we only see a glimpse of in this film, but which was nevertheless there.

Nevertheless, despite these flaws, The Man Who Invented Christmas has a warm-heartedness that befits its seasonal quality. It captures the strange and difficult process of writing in a way that makes this internal procedure filmable, as well as the therapeutic and healing power of storytelling and writing. And, at the core of its warm heart, it carries a message of unification, redemption, and the healing power of the Christmas Holiday. It's definitely a movie I wouldn't hesitate for people to see, despite my scruples.

Nevertheless, despite these flaws, The Man Who Invented Christmas has a warm-heartedness that befits its seasonal quality. It captures the strange and difficult process of writing in a way that makes this internal procedure filmable, as well as the therapeutic and healing power of storytelling and writing. And, at the core of its warm heart, it carries a message of unification, redemption, and the healing power of the Christmas Holiday. It's definitely a movie I wouldn't hesitate for people to see, despite my scruples.

Comments