Dalton Trumbo's Johnny Got His Gun

Only recently, with the anxiety of the election behind us, have I been able to get back to reading. As before, a good portion of my reading--although I know there are some who don't think of it as reading (and they're wrong)--consists of listening to audiobooks. I've always found it amazing what books happen to grip you when you least expect it. Maybe it's the ambiance of a time that causes it.

Regardless, when I was finally able to concentrate enough to read, the book that grabbed me was Dalton Trumbo's antiwar novel, Johnny Got His Gun.

I have been fascinated by the life of Dalton Trumbo for a long time. I was first introduced to him, in passing, by a high school English teacher, who happened to mention one day in class the title Johnny Got His Gun. The title, and the author, both fascinated me, so I set out to learn about him and the book.

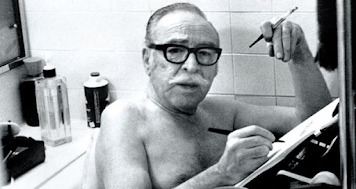

Those of you who saw the 2015 movie, Trumbo, featuring Breaking Bad'-star Bryan Cranston in an Oscar-nominated role, will have at least some idea of why Dalton Trumbo is so fascinating.James Dalton Trumbo was a Hollywood Screenwriter in the Studio Days, who penned films like 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, A Guy Named Joe, and Kitty Foyle. In 1950, with the Cold War ratcheting up and Red Scare Paranoia sweeping the Nation, the Studio Bosses blacklisted Trumbo and the rest of the Hollywood Ten (or Unfriendly Ten), for refusing to cooperate with the House on Un-American Activities Committee. Trumbo spent a year in prison for doing so, as the committee view his refusal as being "in contempt of Congress." (In later years, he said was a completely just verdict as he had contempt for that congress.)

From 1950 to 1960, he was able to find work writing for films under various pseudonyms or with the aid of a co-writing front, including Roman Holiday in '53 and The Brave One in '56, for which he won an Academy Award a piece, before finally breaking the blacklist for himself when his name appeared on the films Spartacus and Exodus in 1960. In his last 16 years, he wrote several more great films, including Lonely are the Brave, Papillion, and an adaptation of his own novel, which he directed, Johnny Got His Gun.

Johnny... however, predates all of this. Years before Trumbo turned to writing screenplays full-time, he published several novels. The first was a novel titled Eclipse, a classic first-novel that drew heavily on his life growing up in Grand Junction, Colorado. His third was The Remarkable Andrew, which features the ghost of Andrew Jackson.

Nestled between them is Johnny Got His Gun, published originally in 1939.

That year is significant because it just so happens to be the year that began WWII; however, it was two years before the United States entered the fray following the events of Peral Harbor on December 7th, 1941. Until then, Trumbo had been an ardent pacifist, hence why he'd written an antiwar book, and they way in which he wrote it clearly communicates this.

Hilary Mantel, author of the Wolf Hall trilogy of books about Thomas Cromwell, has said a number of times that, "A novelist is not obliged to neutrality."

Trumbo, I believe, had he lived to hear Mantel's words, would've agreed.

Johnny...is a political novel, in George Orwell's sense of the word, a book that desires, "to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people's idea of the kind of society that they should strive after." However, Trumbo's way of doing that takes the book from being just political in an Orwellian sense to being outright polemical. At the time of this book's writing, he really didn't want the United States, or any country, to go to war ever again.

How does he do it? By presenting the horror of warfare in the plainest language.

Many writers, when they set out to write fiction, make an effort to show off. They want you, the reader, every so often to stop and think, "Oh, what a lovely sentence. What a gorgeous paragraph. This author must be a major talent." When Trumbo was in the process of writing Johnny, however, it's clear that style, that showing off, was not his goal. He wanted to appall his audience. He wanted to make them see, as if they were looking through the window of Walter Reeve Hospital into a wing full of injured soldiers, exactly how fruitless war is.

Johnny Got His Gun, tells the story of Joe Bonham (a name that makes one think of "Average Joe"). Joe is a soldier awakening in a hospital bed after being saved from the battle fields of World War One. As he gradually regains consciousness, Joe realizes how badly hurt he's become.

He has no arms.

He has no legs.

He's blind and deaf.

He cannot speak, eat, or breath on his own.

He's basically nothing more than a slab of meat, but he's a slab of meat who can dream, remember, and think.

Most of the first half of the book consists of Joe's slow understanding of the state he's in, and we experience that and the slow, horrific revelation with him. Take this passage from the close of Chapter 3, where he realizes he has no arms as he dreams of his the love he left behind, Kareen:

""Goodbye Joe."

"Goodbye Karee."

"Joe dear darling Joe hold me closer. Drop your bag and put both of your arms around me and hold me tightly. Put both of your arms around me. Both of them."

You in both of my arms Kareen goodbye. Both of my arms. Kareen in my arms. Both of them. Arms arms arms arms. I'm fainting in and out of all the time Kareen and I'm not catching on quick. You are in my arms Kareen. You in both of my arms. Both of my arms. Both of them. Both

I haven't got any arms Kareen.

My arms are gone.

Both of my arms are gone Kareen both of them.

They're gone.

Kareen Kareen Kareen.

They've cut my arms off both of my arms.

Oh Jesus mother god Kareen they've cut off both of them.

Oh Jesus mother god Kareen Kareen Kareen my arms."

It's like a curtain being unraveled before your eyes, revealing the crystal clear reality of the scene in the window behind it.

A passage like this shows not only what Joe has lost physically, but what he's also lost emotionally. Never again will be be able to hold Kareen in his arms. Never will be able to hug her, to hold her hand, to cuddle with her under the stars on a blanket on a summer night. Those little human things that we all take for granted--snuffed out in the meat-grinding theatre of war.

Yet, Joe--who is all of us--does not let this stop him. Over the course of the first half of the book, as the realities of his new situation dawn on him, he scraps back every inch of his remaining humanity, a thirsty man who needs that one drink that revitalize himself. Once he's come to turns with his new state in life, now comes the second step of rebirth: learning to communicate with the world outside of his own mind. And he does. This return from the underworld, though, is merely a set up for the later spike of fate that Trumbo has in store for his hero.

Trumbo was aware that if you wanted to hammer a point home, the only way to do it is to be direct. In the passage above, none of the words are complicated, multisyllabic examples of high diction. They're plain speech. He didn't want to disguise his damnation of warfare and the human cost it demands with flowery words or clever metaphors. He wanted his book to be an "axe for the frozen sea within us," as Kafka said.

It is impossible to gage the magnitude of human toll from mere numbers. The only way to approach it, to make it real, is to put a human face to it. Joe Bonham was Trumbo's attempt to put a human face to the horror of warfare. How much can you take away from a man and still leave the man alive? Even if the man remains, will the world give him the respect he's due? The hard questions are what Trumbo struggles with in Johnny Got His Gun, but he provides not easy answers, as any good fiction writer would do. Raise the issue. Ask the question. Let the world figure out what should be done from there.

Who knows; perhaps, one day, we might figure out what the right answer is.

Comments