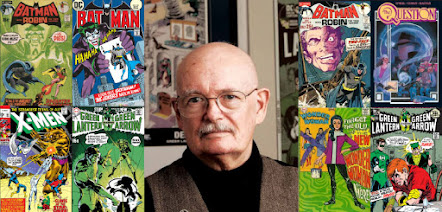

Denny O'Neil and The Question

Denny O'Neil (depicted to the right), passed away on June 11th, 2020, around the time that the US prematurely tried to get back to normal, despite the pandemic still raging. Even if his passing didn't get the attention it should've warranted, people in comic fandom and nerd culture did pay attention and for good reason.

Purely and simply, Denny O'Neil was a writer. He started out his career in journalism before making the jump to go to New York and become a comic book writer. In his time, he wrote for Charlton, Marvel (during its Silver Age), and DC, where he made his most significant contribution. In between such jobs, he also wrote graphic novels, prose novels, and even short fiction, but it's his work in comics for which people will undoubtedly remember him. Frequently collaborating with Neal Adams, O'Neil helped to bring many of our favorite superheroes in DC's backlog back to their former glory in the post-witch hunt era for comics. Among them include Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and probably most significantly, Batman.

As both a writer and eventually editor for Batman, O'Neil ushered in many great titles and shake-ups to the Batman mythos. He reintroduced the darker tone of the character, which had been lost under the influence of the popular, but campy Adam West show and Family-friendly Silver Age tone. He, and his collaborators, helped to create Rah al 'Ghoul, the Lazarus Pit, The League of Assassins, and Talia. He shook up the readership by killing off Jason Todd's Robin and introducing the character Red Hood. He revitalized many of the members of the Dark Knight's famed Rogue's Gallery, including The Joker and Two-Face. He oversaw the editing of the story-arc Knightfall, which introduced the character, Bane, and truly cowed the character for the first time in a physical confrontation, as well as both Alan Moore's The Killing Joke and Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, considered to be two of the most important comics in the history of the character, and much more.

That said, the place I started with to get into his vast body of work was his 3-year run on a lesser-known character called The Question.

I didn't grow up reading comic books. My parents (specifically, my mother), didn't believe that reading a comic book was "really reading," since comics are largely a visual medium. So, my first exposure to superheroes actually through TV, with the DC animated universe, including the New Adventures of Superman, Batman: The Animated Series, The New Batman Adventures, Justice League, Batman Beyond, Justice League Unlimited, and Static Shock. It was in an episode of Justice League Unlimited that I first encountered the Question.

The Question is an unusual character within the DC pantheon because he's not actually from the DC Universe originally. Created by the legendary Steve Ditko (of Spider-Man fame), Question was part of the long defunct Charlton Comics staple, as an answer (pun intended), to Batman. Lacking superpowers, but possessing great physical acumen and a sharp mind, you can see the similarities. However, when Charlton went defunct, DC bought up much of its intellectual property, including the Question. Soon enough, the heads of the company wanted to start integrating these characters into the DC Universe by writing comic books about them.

To start this process, the heads turned to Denny O'Neil.

Already the editor of Batman by this point, Denny had not written a comic book script in about six-months, and his bosses decided it was time to change that. So, they gave him a choice: he could write a comic featuring either Captain Atom or The Question.

|

| The Question Issue #1 from DC |

So, he chose Question—but with one major caveat.

Denny and Ditko had been colleagues when the two of them worked for Charlton. Denny had, until the end of his days, unquestionable respect for Ditko's abilities as a storyteller and artist in the comics medium. However, they completely diverged on political grounds. Denny was a hippie, with a strong sense of social justice and a rebellious streak; Ditko, in contrast, was an Objectivist, a right-winger who believed that the freedom of the individual was the most important thing in society at the expense of everything else. Because of this, Ditko had imbued the Question with much of that political philosophy while he was under the Charlton umbrella, and Denny, as the new writer, could not do that version of the character in good conscience.

Thus, his caveat was that he'd write the Question, provided he could drastically change the character. And that's exactly what he did.

|

| Rorschach from Watchmen began as a satire of Ditko's incarnation of The Question. |

In the first issue of his three-year run, Denny brought back Ditko's Objectivist version of the character and symbolically (the only people who stay dead in comics are Bruce Wayne's parents and Uncle Ben), killed him off. Thus, starting with issue #2, he began to rebuild the character and imbue him with more of a desire for spiritual enlightenment and meaning in life. Like all characters, he stumbles, relapses, and makes mistakes in this pursuit, but he nonetheless keeps going.

This more existential version of the character, who is trying to be a force for good, trying to make human connections in the messed up world he lives in, and trying to make that world a better place for the future is a much more interesting character. He isn't a mouthpiece for a political philosophy; he's a human being, with curiosity, foibles, and an ongoing desire to be better. That, to me, is much more interesting than just a guy who loves individual liberties so much that it includes his right to beat people up (even if they might deserve an ass-kicking).

So far, I'm about half-way through Denny's first year with the character, having begun reading them during the road trip. The art of these comics is fantastic and the story just keeps getting more interesting, largely because Denny was such a skilled storyteller who knew how to use things like dramatic irony, dark humor, and foreshadowing so that every new revelation is a heart render. I can't help but root for Victor Sage/The Question as he strives toward his goal of being better.

My intention is to finish the run of this comic and see how things turn out; if this comic is any indication of what Denny was capable of as a writer, I look forward to reading even more of his stuff in the future.

Comments