"The Are No Rules": My Three Philosophies of Writing

Rules. We all love to hate them—unless you have control issues.

Some follow them instinctively. Some break them instinctively. Some learn them and end up bound by them. Some learn them and then break them with style. And it doesn't matter what field of endeavor you're discussing either, be it dance, stand-up, music, art, or writing.

In writing though, there are lots of rules, given out by lots of people. Some pros, who've come to believe what they say through experience. Some amateurs, who have no talent beyond telling other people what they should do. The truth is, though, that in art (and writing is an art as well as a craft), there are not rules.

I'll repeat that. There. Are. No. Rules.

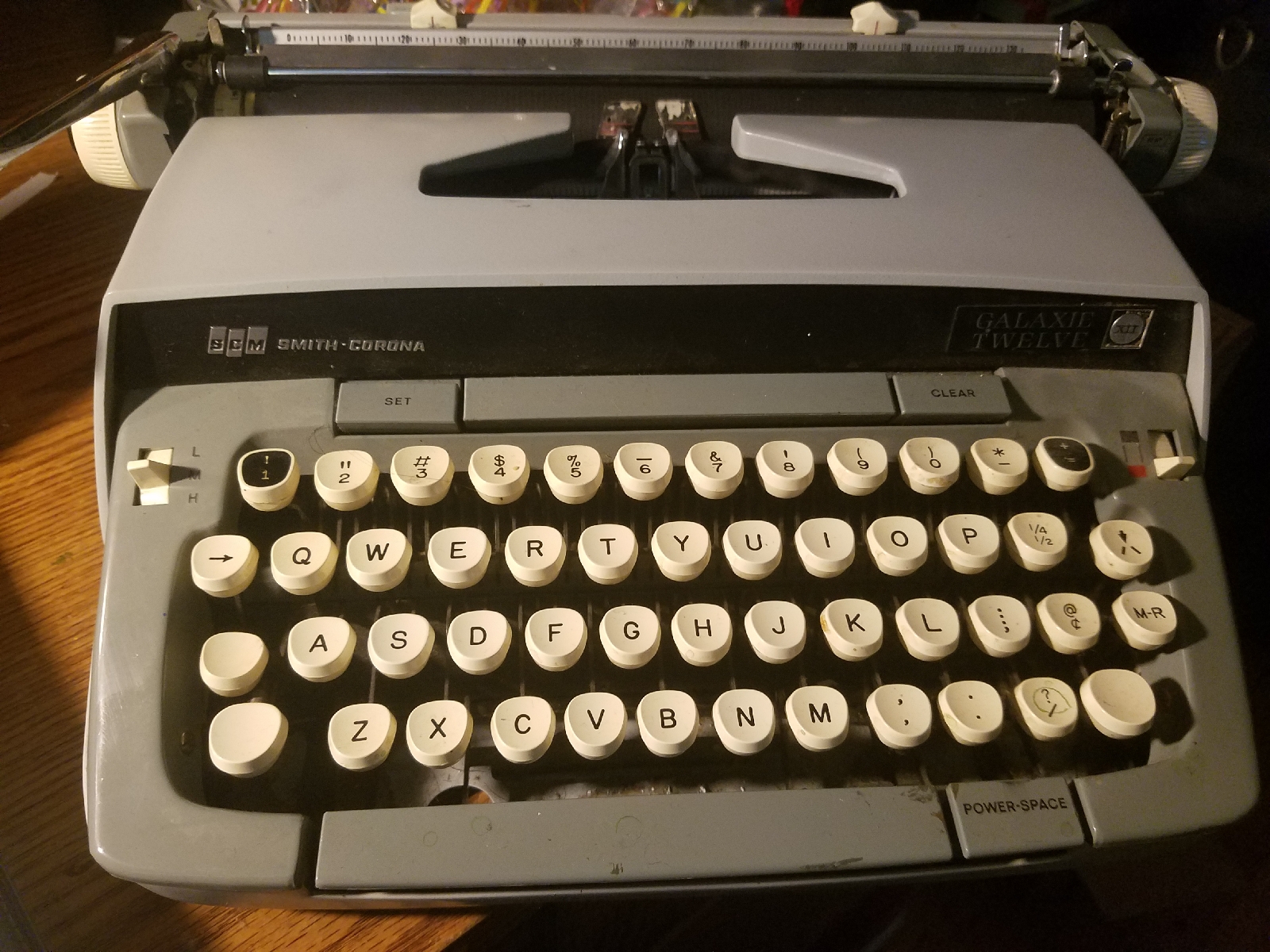

|

| My Typewriter |

At least, no concrete ones that everyone follows. Writers, once we have a grasp of grammar, a sense of the many structures one which we can hang a story, and the techniques we can use to tell a story (all the stuff that makes up the craft side of writing), we all make up our own rules. And then, many of us go on to break those.

Certainly, this has been my experience. Any time when I think I've codified my process, I end up writing a story that throws it out the window, especially these days. So, now, rather than trying to adhere to a preconceived idea of how I write, I trust my unconscious mind to guide me through a story; however a given story wants me to tell it, I follow it.

The upside to this is that I've really stopped looking at other writing advice and begun to trust my own process more; the downside is that, for the most part, I have no more writing advice to give.

Instead, I've developed some guidelines or philosophies, which I've distilled from all the writing advice I've ever digested. These basic ideas seem to run the gambit across nearly every process I've ever analyzed, no matter the author or what they write. Most of all, they're not specifically prescriptive, as most such advice is too "all or nothing," and no two authors work the same way.

1. Everybody does it differently, so do what works for you.

As I said, no two writers work the same way. In fact, no writer frequently writes the same way from one project to the next. Gene Wolfe, the late SF Grandmaster, once said, "You never learn to write a novel. You just learn to write the novel you're on."

When it comes to the craft side of things, there are some many things on could do. The question is which should one do. Answer: whatever helps you finish a project.

Does the story have a complicated alinear that weaves back in forth in time, or are there so man viewpoints that the story feels overwhelming? Maybe an outline could help. Do you just have a bunch of static images in your head that you want to find some way to string together? Try pantsing the first draft and see what happens to connect them. Do you just have a line in your head that won't go away? Write it down and see what happens next.

A writer's toolbox is full of things that are all there for one to use. Figure out what you need to do the job—or even just what you think you might need—and use it.

2. There are no absolutes.

Again, to repeat, a lot of the writing advice in the world is prescriptive, or at least the way in which advisors phrase it makes it sound as if it is. There are exceptions, of course, and perhaps for any given advisor, what they say is always true for them.

The prime example of this comes from Stephen King's On Writing:

"The road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops. To put it another way, they're like dandelions. If you have one on your lawn, it looks pretty and unique. If you fail to root it out, however, you find five the next day... fifty the day after that... and then, my brothers and sisters, your lawn is totally, completely, and profligately covered with dandelions. By then you see them for the weeds they really are, but by then it's—GASP!!—too late."

A lot of writers take this passage too seriously. They firmly believe that they can never use an adverb, lest they mar their glorious prose irreparably. That's crap.

In writing, there are no limits except the ones we place on ourselves. If you think a sentence flows better by including an adverb or adjective, then add it. If you think your novel could benefit from the use of a prologue, add it at the beginning. Never allow the limitations that someone else has placed on their writing to be a burden on yours.

3. Trust your characters.

This one is the most personal to me, and the closest I come to getting prescriptive.

John Irving, author of A Widow for One Year, The World According to Garp, and The Cider House Rules, is a hardcore plotter, so much so that he thinks the idea that characters come to life and change his story is absurd.

In my experience though, I've found that the characters give you everything else you need in a story. A story, when you break it down to its most essential components is "a person with a problem that they're trying to solve." Frequently, the problem is that they want something or, better yet, need something, and they either don't know how to get it or don't realize they need it.

The secret to this is figuring out your character. Characters, like people, are puzzles. You have to look at them from multiple sides to truly figure them out, but even then, you won't fully solve them. But, you may come to understand them. With that understanding of who they are, you'll then be able to see what they might be willing to do to get what they want. There lies the beginnings of your plot. Along with that will come an understanding of the world they live in; once you figure out who someone is, you can figure out how they fit into the world. There lies the beginnings of your setting.

After that, you just have to watch what they'll do.

This is what works for me, of course. Whether or not any of it will work for you or any other writer is completely up to them. But, these loose guidelines have thus far proven true for me. We'll see how long they last.

Comments